Urvashi Vaid – If you leave me… I’m coming too!

It was a running joke with my partner Kate Clinton; she would open a paper and say: “Oh yes, no woman died today” – Urvashi Vaid

Urvashi Vaid passed away Saturday May 14th.

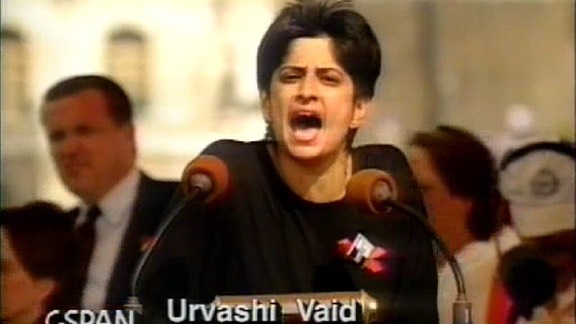

She was one of the brightest human right activists in the US, known for her extensive career as an advocate for LGBTQ rights, women’s rights, anti-war efforts, immigration justice. After working as a media director, from 1989 to 1992 she has been the Executive Director of the National LGBTQ Task Force.

Vaid also worked in philanthropy, for five years at the Ford Foundation, then as Executive Director of the Arcus Foundation from 2005 through 2010.

She was the founder of LPAC, the first lesbian Super PAC, which was launched in July 2012 and as of 2020 has invested millions of dollars in candidates who are committed to legislation promoting social justice. Recently, Vaid was president of the Vaid Group, a social innovation firm that works with global and domestic organizations to advance equity, justice, and inclusion.

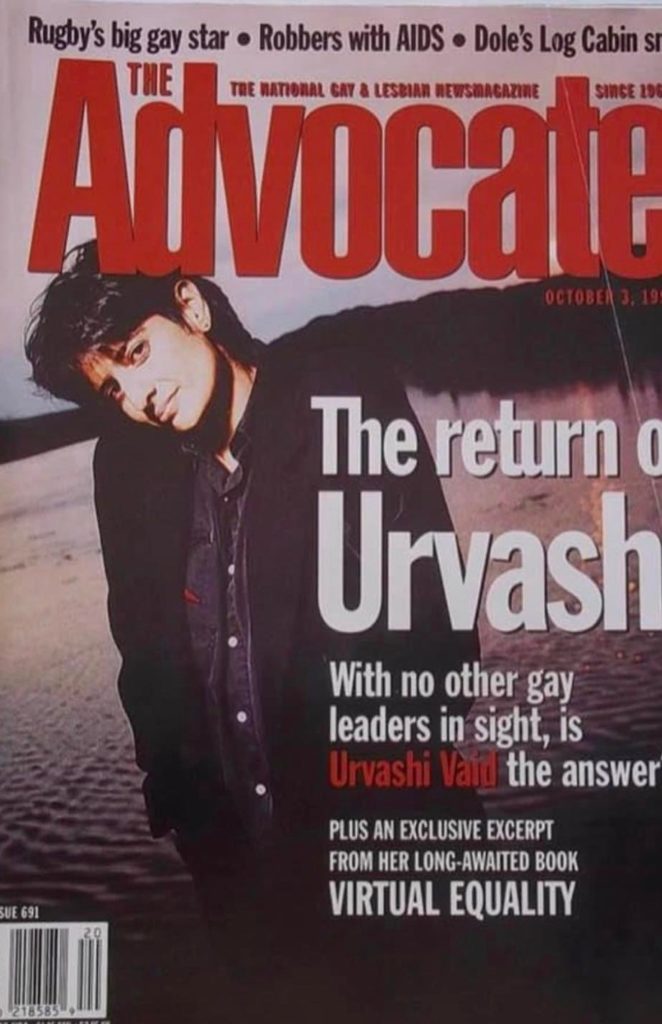

Urvashi Vaid has written several books, among others, “Virtual Equality: The Mainstreaming of Gay and Lesbian Liberation” in 1996 and “Irresistible Revolution: Confronting Race, Class and the Assumptions of LGBT Politics” in 2012.

With the EL*C team we had the great chance, back 2018, to meet her in NYC. We talked mainly about lesbians, politics and the media.

Besides of being very smart and having a gigantic experience in activist, she’s also one of the funniest persons in the universe, so it was sometimes a serious discussion, sometimes just a succession of jokes and laughter.

Here the notes of the interview:

(Alice Coffin) – The first question is about LGBTI visibility and more specifically lesbian visibility in the media. How did all begun and how it has evolved from your prospective?

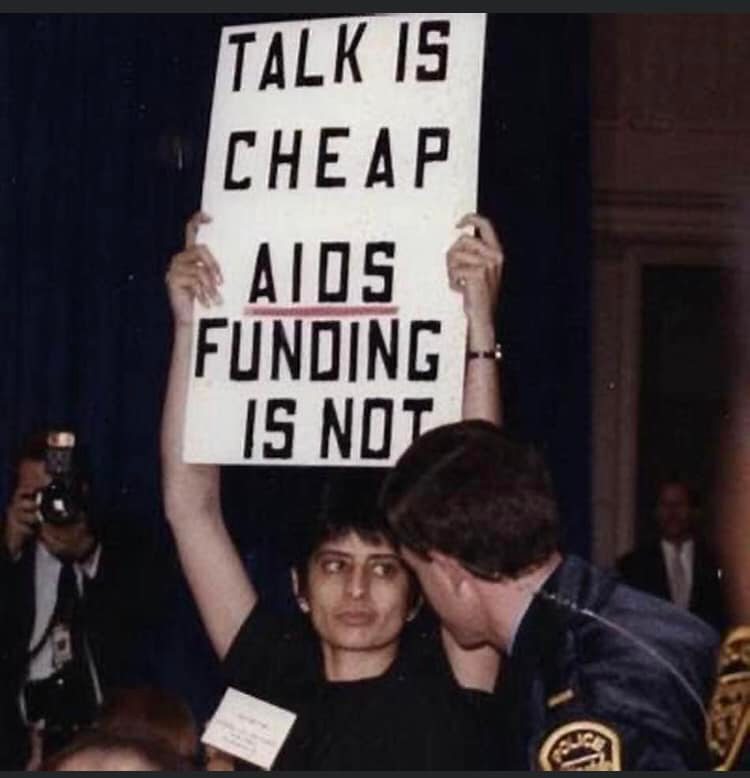

Urvashi Vaid – I understand. Well, it’s a big question and I think we can look at it from different angles. Are you specifically interested in lesbian issues or are we talking about getting covering for LGBT issues in general? Um, I personally think it has been very broken through and very assimilated in the cultural space and much less so in news media. It would be interesting to think about how that has changed historically. When I started out – one of my first jobs in the movement was communications director for the national gay and lesbian task force from 1986 to 1989 – it was an era in which you rarely saw a story about LGBT people. There were no LGBT characters in movies and television shows – well, if there was, it was a big. It was a news item: ABC shows a gay character, big news! Oh my God, they showed a kiss; what will happen to America?! They kissed on TV?? [she laughs]. I think that [started to change] in the late 80s when the media started to do women entertainment and started to do AIDS stories. That was a big news, and our job at that time was to try to get the news media to cover it. Our job was to get the news media to cover the HIV/AIDS, to cover hate violence, to cover the policy work that we were doing in Washington, to cover the movement around the country… And that was pre-Internet. I used to physically send out press releases twice a week: I had volunteers who came in and stuffed and folded them; we mailed them out. And I made phone calls and did one on one meetings to build a relationship with the journalists, with the Washington based press core. I also did a lot of work on trying to get coverage around the country for demonstrations that were happening in Washington, like the Act Up demonstrations against the Food and Drug Administration in 1988. I was working with the Act Up Media Committee and we got great coverage because we had a whole strategy with Mike (Michelangelo Signorile). For almost a year, I only knew Mikk by phone. We had never met until the day of the action. We planned that whole thing [she laughs], and he was brilliant. The people in Act Up New York were great with media because many of them came from New York Media – he was in the gossip columnist world. And I was working at the task force as the media director. I reached out to all the regional media saying: “look, hundreds of people from all over the country are coming; you can get a story for your paper back in Nebraska; for your paper back in…” We literally had them hold signs saying where they were from and then we said to the media: “look, if you want people for your regional newspapers, go under that tree and find them” [she laughs]. It was very rare that they would get a local story at the national in Washington, so they were very hungry for it. And it’s all these chains at that time… You know, the Scripps Howard which served 50 newspapers and 50 different markets had three reporters covering that beat. Anyway, I feel like it was almost easier. As hard as it was back then, it was easier [than today].

(A.C) – How did the journalists react to your one-on-one meetings?

U.V – It was a little bit of a mixed reaction. The health reporters were very interested. They had a beat to cover health and AIDS was emerging, so they were really interested in stories and happy to take your card and talk to you about it. You know, they would call: “hey, I’m doing this story on public hospitals and how they’re handling HIV, do you know people who have been patients in public hospitals?” And then we would work with the AIDS organizations and get them stories. The other thing I did was we had a coordinated phone call that we started to do with a couple of the LGBT organizations and about five or six HIV/AIDS organizations: Gay Men’s Health Crisis Media Director, San Francisco AIDS Foundation, a person in Chicago, somebody in LA, somebody in DC… We would get on the call and talk about what kinds of stories we wanted to generate in order to help advance the advocacy that we were doing. The idea was: we’re trying to get the Ryan White Care Act passed, so let’s get some stories about the need for these services in different communities. We worked with the health reporters, the municipal reporters… Wherever the beats were. But it was a coordinated approach.

(A.C) – So you went for specific beats, and even outside the LGBT news media?

U.V – Exactly. But we were specifically LGBT identified, so we were going there and saying: we would love you to cover the LGBTQ… I mean, we did so many strategies to try to get coverage. There was a local strategy for the Washington Post for instance. At one point, a bunch of us activists realized that The Post wasn’t covering the local community. So the Gay Activists Alliance – they became the Gay and Lesbian Activists Alliance by the late 80s, and they’re probably the LGBTQ Activists Alliance today, I don’t know [she laughs] – which was a advocacy volunteer group in Washington DC, started to have meetings about that. I was at the task force about the local coverage and the lack of coverage and we came up with the idea of doing a monitoring project for six months. We monitored their coverage and we wrote up a little paper, asking for a meeting with the editor in chief and their senior staff. We said: “during the six months, this is what you covered, and during these six months this is what happened and what you missed. We’re the community that you serve, and there are dozens and dozens of stories that you’re missing.” That was our approach at that time. We said: “we are your neighbors, and we would like to educate your reporters about who the community is”. I mean, it was hard on the reporters’ side: they were so many people were closeted they did not know who to reach out to. And most of the organizations didn’t have paid staff – the larger ones, on the national level did, but the local ones were all volunteer – and so they would complain that they didn’t know. So, we did a few briefings and trainings with journalists and editors. The angle was: “you should know your community and we can be a resource for you. Here’s a resource list with different organizations representing the diversity of our community, with contact names and phone numbers so that you can easily connect.” I think we didn’t have the wherewithal or whatever to do a follow up two years later, but I would have loved to have seen whether it changed anything. But the reception was positive and there was a little bit of a spike in coverage – certainly there was more openness than in the relationships that had existed before. These efforts were made in the 80s and in the 90s, before the anti-gay backlash grew. Then the stories changed. They became much more about including that voice. You know, journalists certainly didn’t quote us every time someone said hateful things about gay people. But now, they felt compelled to quote the hateful people whenever there was a positive things to say about LGBTQ people. And I think that whole balance doesn’t work; I mean, it’s very imbalanced. Whenever we’re covered, whenever the underrepresented subject is covered, then the other side has to have its fair play; but when the mainstream blasts on about its homophobia and racism, they do not feel compelled to include the critical voice…

(A.C) – Is this why you said it was easier, back then?

U.V – I was gonna say it felt easier because of…Well, the change is technology today. Even with the clutter of my press release sent to hundreds of journalists, it still wasn’t tens of thousands of others. Email has made it possible for a reporter to be blasted with so much information… And with the digital space, they’re able to access anything, anywhere at anytime from their station. I think it has made them at once more informed and lazier. They are more informed because they can look it up; but they’re lazier because they don’t go out there and develop new stories. They don’t call you and they don’t have relationships with people like me. In the current infrastructure of the organizations, I would venture to guess that most of them don’t have those relationships with the leaders, much less with the communication staffs because they’re so busy; in this digital environment, you have to work at a much faster pace. You have to respond instantly. You have blogs that you’re supposed to be doing; you’re supposed to be posting on a deadline that is compressed. In the old days, it used to be: “you have to file this by tomorrow morning at 4:00 AM.” Now, it’s: “I have to file by 4:00 PM in order for it to be there in the 6:00 PM and then I have to react, update it by 8:00 PM”. It’s just a whole different pressure on the reporter. And I think it’s harder because we’re competing with more information about everything. Also, the sourcing has changed, right? Journalists don’t just go to primary sources anymore; they will go to a Facebook post or a blog post and use that. Maybe that’s good, but I don’t know. I think that news media should go to primary people and not just repeat something that somebody said and call it news. I think it’s important to have openly LGBT people in the media, but their presence does not in and of itself increase coverage or change the quality of the coverage. That is interesting. I mean, the New York Times is essentially full of very important prominent gay men – mostly gay men, far fewer lesbians; hardly any trans people and very few people of color. So, it’s predominantly white gay men who are in the leading newspaper in this country. The Washington Post might disagree with that calculation, but they still haven’t changed their coverage around people of color and it hasn’t increased their coverage around women. They cover many more stories about gay men than they do about women, in every section of the paper: business, sports… And it’s true for LGBT people too. They cover many more about gay men. Here… I mean, it’s the same problem that we had with the Washington Post. There’s a huge community here in New York. It’s a really diverse and active community. People are organizing in Queens and Brooklyn. They’ve got local issues and that paper doesn’t cover it – and, frankly, neither do the other newspapers like the New York Post or The Daily News. And I’m just talking about newspapers here, but most of the television and radio doesn’t do it either. The people who do cover it are the queer press and, to some extent, whatever might be characterized as progressive media. So, I haven’t done a media study in a while, but if you were to do a next of search it would be the fact that there is a larger number of news stories in the New York Times today than there were twenty years ago, or ten years ago, [but it does not necessarily increase the coverage of these issues.] This would be interesting. I think they spike, of course, like when the Supreme Court marriage case was happening, there were bunch of stories that covered that issue. So perhaps it’s tide more to a crisis or an issue. But yeah, even what’s happening with the Trump administration right now over the last two years… I think that there’s been very few stories in the mainstream media about the impact this administration has on LGBTQ people. There’s been stories about it, but I don’t see that many.

(Silvia Casalino) – Yesterday, while we were driving, we were listening to a radio which was doing very good on these issues…

U.V – Yes. NPR, the radio does very good coverage. It’s true, I will give you that.

(A.C) – I feel we don’t have the same relationship to the radio in France…

U.V – Yeah. It has an audience; there’s a lot of people who listen to the radio but it doesn’t get talked about, unless somebody writes about it… I really am jumping around, I’m hope I’m giving you what you’re interested in.

(A.C) – What was the reaction of your community in front of what you were trying to do with the media? In France, I have difficulties to explain why we should seek visibility and frame things in a particular way – the only way that would allow us to have an article. The community often thinks that visibility is not the issue or that we need to ask for more radical things…

U.V –I mean, we were invisible for so long in this country – and some would argue parts of our communities still are invisible – that media representation was an early focus of the movement. It was an early priority to get reported on and to get coverage, and then to challenge the coverage to make it less biased and less stereotyped. […]. So I don’t think we had to fight to have a focus on the media. I mean, double A GLAAD – we call it double A GLAAD because there is a single A GLAD in Boston, just called the Gay and Lesbian Advocates and Defenders – was formed to challenge the stereotypes that were being promoted in the news media about LGBT people. So, they did style sheets: “this is how you should write about us; when you refer to the community, don’t say homosexual, say gay…” These style sheets eventually became mainstream, but it was a revelation when they started doing that in the 80s.

(A.C) – The equivalent of GLAAD was only created 4 years ago in France…

U.V – Wow. Well, I think in France there this kind of attitude … The French are so worldly and think they don’t have the problems that Americans have. But I’ve been insulted as a lesbian in Paris. I was walking hand in hand with my girlfriend, and I was shocked. I just looked back at the guy, a well-dressed man with his girlfriend who just insulted me. I practically punched him. It was at L’île Saint-Louis, ridiculous. But it’s the point: the bias against us is everywhere, in every country, in every culture, in every community. So, maybe the French attitude lets them think you don’t have this problem there…

(A.C) – Also, it’s very difficult to not look biased as a journalist if you’re out… And “community” is a dirty word in France. They say: “you have to be neutral to be a good journalist, a good politician or a good teacher.”

U.V – Well, it’s happening in here too; this whole idea that… You know it’s a backlash against identity politics. How it’s expressed here is that identities have been fracturing and they blame identity politics. And I say: “Yes, but you know what identity is? It’s a 2018 year-old Christian movement, a multi-century old white identity movement.” [She laughs]. I mean it isn’t the 50-year-old lesbian identity movement that is causing the fracturing of America, give me a break [she laughs]. The blacklash is just everywhere and is told again and again by many people in the progressive world. They say: “race, gender, sexuality have been a distraction from the true fight, which is against economic inequality.” To which I always say: “well, show me the true path forward. What’s stopping you? Tell me what I should do.” They have no answer [she laughs]. And I mean, it’s so insulting because these are movements around race, sexuality and gender identity have been the ones that have been raising issues of economic oppression and inequality. It’s not like they’re sidelined on those issues. But there’s a big backlash against identities and saying that we didn’t speak enough to the mainstream, and that’s why the Trump phenomenon came up: we didn’t address the anxiety of the white men who were losing their jobs in the Midwest. Again it’s a rewriting of history because we were marching and protesting against NAFTA. I ran the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force at the time – I became the Executive director – and we took a position against NAFTA. You should have heard everybody criticizing me: “why are you at the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force taking a position against NAFTA? This has got nothing to do with gay and lesbian people.” We were talking about neoliberalism, about globalization in the way that it was being done by Clinton being problematic. And it’s ironic… if I were to have the energy to go backwards and look at the people who were criticizing me and read their quotes today about Trump, they would all be Republicans who are falling over backwards to praise him. [She laughs]. The point is not that I was right, but that there were a lot of people in progressive spaces who were the people who were criticizing this global economy that was taking things away from people and displacing them and putting pressure on other countries, as well as giving opportunities and building up middle classes around the world. You know, neoliberalism has been a very complicated experience. So Trump comes along and is the voice that is criticizing that, 35 years after it happened. But from the right. And there is a base that’s been building. It was a labor union base. It was a progressive base, and it did hear him as the one candidate who’s speaking about this, while other candidates weren’t. So, you know, it’s complicated. But, also, the appeal of Trump is very much about racism. It cannot be overemphasized. Race in America is the central organizing principle. It’s the core of this country’s history: 400 years of slavery or war and it’s written into the Constitution in ways that have to be undone. There are these reactionary origins of it. There was a civil war in this country about race; it’s deep. And it continues to unfold in amyriad ways for black people. There is structural racism that’s very specific, anti-black racism in this country. And then with immigrants, which is kind of a global phenomenon, the anti-immigrant sentiment. It’s pretty much the same argument whether you’re in France or whether you’re in Germany, whether you’re in America, you know: “we need our jobs to go to our native-born people.” But here, in this country, everybody is an immigrant except the Native Americans – brought forcibly as a slave or as an immigrant. And that’s quite a history, which is conveniently ignored. Trump’s family from Germany. He’s like a second-generation immigrant. So, it’s so deeply racist because what they’re really objecting to is brown and black people coming over. And scapegoating them. And again, I used to hear these conversations in Michigan, when I worked there for a while, running a foundation for somebody; I would split my time between New York and there… These locals would be going on and on about: “we got to have better immigration laws and closed borders” But the kinds of jobs that immigrant laborers were doing in that state were not jobs that the white people were doing. So, again, it’s just not rational, it’s just emotional and pure racism. But how does the media cover that? They are covering it pretty poorly, in my opinion. They’re covering this story right now with the children being separated from their parents, and some are making the connection, but I mean it’s such an overt example. In many ways, Trump has forced media to do more than they were doing. I would say so. But still, they give him so much space and authority…

(A.C) – Why?

U.V – They are afraid because they get attacked. And that fear keeps them from really going after him. They don’t go after him – except, I mean, the Washington Post has been doing certain stories, like the Russia investigation – but the guy is so corrupt; it’s so hypocritical. Did you see the other side of it? What they did to Hillary? There’s a few deep pocketed wealthy right-wing moguls who bankrolled some attack machines that spent eight years while they were in office attacking her – and has continued ever since. Hundreds of people were hired with the specific job to dig up dirt, write columns, do nasty books, spin lies, etc. And newspapers traded on this; the mainstream media would cover those stories when they became kind of rose up. They repeated them, and they amplified them. And there’s nobody doing that for Trump on our side, I can’t point to a single media who is saying: “we’re going to dig up dirt to attack President Trump’s self-dealing, cronyism and corruption.”

(A.C) – All that because of fear?

U.V – Well, what’s stopping the billionaires on our side from having the guts to take them down? I think some of them think they are. But like the other side, I don’t know. We feel that it’s pretty ineffectual right now. The resistance is not organized. It’s is coming from, not the organized sector, but truly the people. I mean, that’s the most amazing thing about America right now. There is a resistance and it’s ordinary people who have never been politically active like this before – or not in a long time. They are people who really feel threatened and urgent. That’s who is on the streets in the women’s marches, both first ones and the second ones; millions of ordinary women and men. I don’t know if you agree, maybe… But I’m not idealizing. I mean, you see it is. Even the political fight that we’re having right now. The Democratic Party’s narrative about what they’re doing isn’t true. If you would go out to the country and talk to candidates, they’re not getting help from the party. The real insurgent candidates that are running, the women who are taking on these incumbents, the lefty people who are challenging the right-wing zealots everywhere… They were not encouraged to run by the Democratic Party or by any party. They kind of did it, and they have worked through these new infrastructures that have popped up: swing left, indivisible, stand up America… There are millions of people who are connected now through these new oppositional infrastructures – which are channeling us to say support this or that; I mean, that’s what our PAC is trying to be.

(A.C) – Could you tell us more about that?

U.V – It’s a small political action strategy we started five years ago, before Trump. The idea there was lesbian visibility and representation, both in politics but also in political spaces. Many of us who are queer women – we had been very active in the movement, but we started talking about three things: 1) being in space after space where we were one of a few women; in political meetings in political fundraisers, in meetings with elected officials… 2) the fact that our LGBTQ organizations don’t carry forward a feminist agenda, even though people like me have spent 40 years working to build an LGBT movement. Most queer organizations aren’t explicitly pro-choice; they’re not fighting for equal pay for equal work; they don’t really focus a lot on violence against women. You know, they might be talking about hate violence or bias motivated crime, but they’re not talking about gender biased motivated crime and. That’s really astonishing. 3) The third kind of spark was that in 2012, we had a lesbian running for the Senate for the first time, Tammy Baldwin. She actually won, but it wasn’t a given that she was going to win. She was a local political leader in Wisconsin, and she decided to campaign for statewide office and a national office, and for the US Senate. She became the first openly queer woman to be a senator. And she’s running for reelection again. So, you know, six years ago, we were looking at that and saying: “well, this is an opportunity: she’s running, we can galvanize around her and energize women to get more involved in the political system.” And that’s when LPAC started.

(A.C) – Who was there at the beginning of LPAC?

U.V – It was me and about a dozen other women, all of whom were pretty experienced hands. We had all worked in different organizations and some were wealthy donors who had deep pockets. Some of us are activists and organizers, you know, with networks and connections. So we raise money, we endorse candidates, we give the money to candidates we get behind and mobilize our community to support them. We can even endorse straight women, but they have to be the same positions on LGBTQ rights, on women’s rights and on racial and social justice issues. We do questionnaires and we try to evaluate the person. We’re looking for champions.

(A.C) – Are there good individuals in there?

U.V – Yes, there are good people. In the 2018 election cycle, what’s unusual, in my opinion, is that there are more queer women running than ever. There’s queer women, trans women running… That’s just really impressive. I think that the misogyny is so vivid people are really fed up with it. I mean, one of the candidates we are supporting is a woman who’s running for Attorney general in Michigan. Her name is Dana Nessel and her first ad… You wouldn’t believe it. You should look it up, just Google “Dana Nessel penis” because her ad was basically her looking like a politician sitting in front of a fireplaces saying: “if you really care about ending sexual harassment and sexual violence, don’t vote for anybody with a penis. I can tell you one thing, I won’t harass anybody. I can promise you, I won’t.” It was shocking. It was shocking because nobody says that. And she got a lot of attention; she now has the Democratic nomination – she’s the Democratic candidate for Attorney General, whether she will win or not. She was a District Attorney, and she has made herself into a real contender. She was bold, and she took risks.

(A.C) – What do you think about the matter of visibility? In France, when we call our group a “lesbian” conference, people say it’s not inclusive enough…

U.V – [She laughs]. We get that all the time. But we’re very inclusive. LGBT, women, men: welcome. We’re open for everybody. We have a special category even for the guys, we call them “lesbros” [she laughs].

(A.C) – Many people don’t even know the term “lesbophobia”.

U.V – You know what you should do? You should develop little flash cards with a picture of all the stereotypes of lesbians and just hold them up to people and say: “what’s the first word that come to mind?” When they answer: “lesbian” you say: “that’s lesbophobia” [she burst into laughter]. Visibility has been a debate here too. For many years, that was such a big goal because we were not visible; I think visibility was critical for the LGBT movement but that the biggest source of that visibility wasn’t the media. It was ordinary people coming out. You know that’s when that hit critical mass. And I think that happened through the AIDS epidemic: people were outed or challenged themselves to come out because they couldn’t stand by anymore. So that was one huge way of emerging in this country. And then when the right-wing backlash really dug in in the late 80s and 90s, that was another big wave. I mean, the 1993 March on Washington was very large, larger than ever. Because there was such a repressive backlash and and also there was a Clinton moment. People were like: we have a moment, we gotta do this. And then marriage was another wave of emergence because for a whole lot of other people who had not been particularly active in the movement, it became their issue; it was important to people because it was very personal, it was about their relationships and about their families. So, there was a big discussion in our movement about: is marriage selling out etc.? But in the end, I think marriage turned outlaws and in-laws right? That’s the line. And it was a good thing. We were sexual outlaws, and we became everybody’s in laws. [She laughs]. Quite a trick. But visibility is never enough, and you have to have some kind of representation, and in decision making places and institutions and you have to have power. To be able to push for the agenda that you want and to hold politicians, public officials, and corporate leaders; everybody accountable. So you need a movement. But then, you know, for journalists it’s complicated because you’re supposed to be “above it all”, not of the movement. What happened to the whole tradition of crusading journalist? You know, where journalists who saw slums for example started writing stories about landlords and said: “why is this landlord getting away with this; why isn’t City Hall enforcing the code against this landlord? Is it because the landlord paid the politician $50?” I mean, that’s a story. And that’s crusading. It’s crusading on behalf of people who don’t have a voice, or who wouldn’t have the power in that situation to be heard. Journalism has power, and journalists have power to amplify the voices of people who may not have access to that microphone. So, yes, you have to have judgment., discretion or discernment about what’s real and what isn’t and not being manipulated as a journalist, right? Whatever, I understand that. But I still think that the power is underutilized to tell the truth or to expose things; to shine a spotlight on a problem or a situation. There are multiple moments in the life of any city or in the life of any community where some people are being exploited by other people. I would say that the role of the journalists is to shine a spotlight on that and share it. If you’re writing an op Ed, you couldn’t have a judgment about it, but even if you just wrote the story and said: this landlord is charging these people $5000 in a slum and isn’t being investigated by the fire department because they paid the politician…” That’s a story [she laughs]. Anyway, I I’m telling you what you already know […]. The other thing was that one of my earliest experiences was working with a group called Gay Community News, GCN. It was a progressive newspaper, an incredible paper started in Boston in 1973 – I moved to Boston in 1979. The LGBT press was the ones that covered our stories. And GCN was rarer in that it was feminist and progressive so it would cover abortion, women’s rights, marches and demos and lobbying; it would cover the South African struggle… It was through GCN I learned about Simon Nkoli who was a gay activist in South Africa and about the role that these activists played in the ANC. GCN was one of the papers on our backs; Fag rag was another paper that was really radical for gay men in Boston. GCN had a collective, a structure and a staff. I think that the papers like a Gay Community News and Philadelphia Gay News and Washington Blade were the ones who were covering gay men and lesbians getting kicked out of the military, and different purges that were happening. You hear the story in the gay press, not in the mainstream media. They’ve never covered it. They were covering the stories of what was happening outside of gay bars and all the violence and the beating up and stuff that was happening. They were covering internal stories about domestic violence in the gay community. They were covering the contradictory parts of being queer, too. So, I really think the LGBTQ media is essential. You know many people I’ve talked about that over the years were asking: it “passé”, is it over? A number of outlets have closed, but there’s a flourishing in the digital space of queer media, blogs etc.

(S.C) – Is the LGBTQ media influencing the mainstream media?

U.V – I don’t think we are. I don’t think they’re taking up the stories, in my opinion. This is where we will go back to my earlier comment: have LGBT people in the mainstream media been particularly helpful? I think a lot of times when you’re a queer person in a straight environment, you’re proving yourself as being more than a queer person, and it’s the same with: “I don’t want to be just known as a woman” or “I don’t wanna be just noticed for my color”; “I don’t wanna be just known as a lesbian., I’m a journalist, I’m a lawyer…” So there is sometimes there a kind of a resistance against covering your own identity. But yeah, I feel it would be another interesting experiment to look at a month of headlines in the Washington Blade and then to look at a month of stories in the Washington Post to see if theretis any correlation. Maybe it’s the same. I mean, the gay press today is covering much more – the same landscape that the mainstream media coverage: we’re covering Trump, Congress… But they’re still covering stories that the mainstream doesn’t cover. Like the murders of trans women for instance. It’s a huge issue but they don’t care, or they might cover it as a simple “murder” without any connection [to society at large.]

(A.C) – In France, there is no journalist who is specially cover LGBT issues; they’re only “general” journalists.

U.V – Wow. But they don’t cover deep, they don’t get the relationships, the understanding of the community… I actually felt during the 80s, during AIDS coverage that the best coverage came from these reporters who had developed deep relationships with the advocacy community, with the health care providers, so they could go deeper into the story. And that was true for broadcast as well as print reporters. There was a guy at ABC named George Strait, who was great. He was the health reporter for ABC News. He did so many stories. Everybody knew him; he was really opened to hearing a good story. Robert Pear too; he’s still writing for the New York Times. He did so many stories about Medicaid and Medicare and poor people and HIV. He’s still writing about that, by the way, because this is his beat; but I will forever respect him because he really was a serious journalist. There are so many stories to be covered about our communities.

(A.C) – Do you have any theories as to why these issues might seem as less important?

U.V – Well, we could make up some stories, some theories. For a paper like the New York Times, they’ve always had huge blinders around gender or race and sexuality, and they still do. I don’t know if you saw this, it was fascinating… There was this large mea culpa thing about the New York Times obituary section; they wrote: “Oh! We don’t cover a lot of women. We’ve just discovered that.” It was just… I actually had launched a campaign for them to do an obituary for my mother and failed. I was furious about it and then, you know. Anyway. That little mea culpa is an illustration of the blinders around, gender. Even there, they don’t see dead women. They don’t see live women, and they don’t see dead women [she laughs]. And they don’t challenge themselves to ask themselves if their coverage is biased, because there’s an assumption of neutrality. But it’s just patriarchy. Can we just say it? It’s just patriarchy. You know: “when we say men, we mean women too.” That’s the culture I grew up in. You’re a little younger than me, I’m almost 60. Everything was he; he meant she. And still, this whole gender pluralism that we’re living through… It’s not in the mainstream. They still basically are interested in stories about men because that’s who their market is.

(S.C) – We have a friend, Nelly Quemener, professor and researcher at the university, who is working, as usual, from a lesbian prospective with a lot of irony. She said – because there is no lesbian obituary going on in the media, press or TV – lesbians must be immortal. [They all laugh.]

U.V – Yeah, yeah. I mean it was a running joke with my partner Kate; she would open a paper and say: “Oh yes, no woman died today”. [They all laugh.]

(A.C) – [Briefly recounts the reaction of men who find themselves facing an action of the French feminist collective La Barbe]

U.V – I think they also don’t see women as actors in the public sphere. They still see women in a privatized way, as mothers and wives – which we can also be: mothers, wives and public actors. But I’ll give you an example. Years ago, when Andrew Sullivan was editor of the New Republic, I reach out to him. So, it must have been maybe 1992. And we had lunch and I said: “I like your paper, but you don’t have many women writing for The New Republic…” And he said to me: “well, there’s not very many women who write political commentary and analysis”. I was like: “did you just say that?!” and I sent him a list of women’s names. I mean, his reaction was: “why don’t you write for me?” and I wrote a column and stuff but… That was like a liberal guy, and that was his immediate response. And I’ve had other journalists over the years saying variations of that, and that they can’t cover female issues or lesbian issues because “they don’t really understand the issues.” And I’m like: “I could not get away with saying that” [she laughs]. If I said: “I don’t cover men because I don’t understand the issues; it’s too far from my experience…” But I think that is true. I think that was a truthful statement. This man wasn’t being mean or weird or anything. He was being honest, and I think that’s true. So, in the New York Times, there are reporters who are gay men and who are unable to…

(A.C) – So the problem would be in hiring?

U.V – It’s a hiring issue. But it’s not just in the hiring, it’s also in the management. I mean, whatever passes as management for journalists. I mean, the editors edit, but they should also be developing the capacity of a writer to be more well-rounded. But they’ve always been owned privately. And the old, fear was advertising – and still it is: “if we do this story, there will be a boycott from the right wing…. We can’t be too pro-gay.” A lot of public companies didn’t come out for LGBTQ rights, because they were afraid of being targeted by the evangelical right, which has millions of followers. But now, the Trump fascists have turned the complaint of “bias” around brilliantly with “fake news.” Everything they disagree with is fake news. The only truthful news is their lying organs that the world that they’re Saints. It’s just classic fascist playbook. And it has happened. But there are other examples around the world: Berlusconi owns the press, which is what you’re talking about. You have politically minded people owning media. But then we have politically minded people owning media on our side, and I go “yeah” for them so it’s kind of contradictory for me to say that.

(S.C) – I was thinking about what you were writing 1995 when you talked about the conflict between the mainstream media and the new radical institutions… What did you mean by that? And what are your feelings now on this topic?

U.V – I think the mainstreaming has been… Not enough. It’s a first step, but we haven’t really dislodged the underlying revulsion among many people towards us; we haven’t changed religion; we haven’t changed government; we haven’t changed the laws enough. So I think that the argument I was making there was that mainstreaming produces this kind of virtual equality – a simulation of equality; but the only way to get real equality and real freedom is to restructure the institutions in our society. And that’s a longer and harder struggle of power building and aligning with other movements and building a true political, cultural, economic movement, Do I think it’s possible today? I mean, capitalism has so won. Now I say: “we’re trying to get socially responsible capitalism”, which is a contradiction in terms, but so it is. [She gives A.C & S.C one of her books; “five people read it, it’s ok.”] This book is really more practical. I’m trying to problem solve the ways that we can get a movement to address issues of race; to get movement focused on poverty; to get the movement focused on criminalization or gender or gender identity or women… I mean, that’s what I do. That’s what I’ve done. We have different projects and different people that are working on some of these areas.

(S.C) – Do you think it’s a good thing that we still have that discussion on whether we should try to lobby politicians etc. or not?

U.V – Yeah, absolutely. I think this is still a live conversation and I don’t think it’s an either/or. I argue that “virtual equality” isn’t sufficient. Litigation and lobbying advocacy are means; they’re not the end goals. And equal rights are not the end goal. A society in which women have dignity is the end goal, you know. Women have equal rights, there’s still misogyny and violence and pervasive suppression of the female gender – or women of all genders, we could say. What will it take to have that change? It will take masculinity to be transformed. And that’s my beef with the LGBT movement. Really, they have done nothing, the gay men have done nothing to deal with masculinity; nothing. For a minute, in the 70s and in the 80s, there were discussions about these matters. There were radical gay men who were talking about: “I don’t want to be a man like I was raised to be, and being a man is so much more than this gender performance”, right? But where did that go? And I think, in order for women of all genders to be free, masculinity has to be radically changed. And that’s the job of men too. But I don’t know if I’m answering your question without being too theoretical. I see it through the conceptual framework that I believe in and, you know, I love the new movements in this country: the movement for black lives, the human rights movement… These are truly radical movements. And they do see the transformation – that race will require real different power structures. That’s what I agree with, this structural problem. And that’s what we’re up against. You have a backlash from those people who don’t want to give up power. Power does not yield easily. Nobody wants to give it up, they feel like they’re gonna lose something or that they’ve lost something because of us. When the truth is that the people who voted for Trump who lost their jobs in the Midwest. They didn’t lose it because some lesbians got to get married. I mean, it’s ridiculous. They lost because you know, a bunch of straight guys made a decision to get richer by moving their factories overseas and paying Chinese people less. [She laughs.] Why don’t we have a blunt talking politician who says that, like Trump says it? Trump says it on the other side: you lost your jobs because these gays didn’t care about you. They let it happen. It’s a crime. But Trump was right there, benefiting from it happening.

(S.C) – We had a discussion with the President of the Columbia Journalism Association… He was shocked by our situation in Europe. What was the #MeToo movement like here? It just seems so different between France and the US.

U.V – It’s true. It’s funny, isn’t it? Because in the 70s there was a very big conversation. Brownmiller’s book came out, “Against Our Will”, and there was this big discussion about violence and rape. People were saying we should take back the night marches, take back the streets and challenging violence in the streets. But the movement moved very quickly to police violence against women, and that lipped over the cultural change that we needed, in a way. They said: “if you can, just call the cops.” Like, the hospital bed restraining order… I mean, we’ve done that for years and it’s doesn’t work. It doesn’t. But again, what’s at play is masculinity and power and domination. That’s not going to be addressed by a law criminalizing domestic violence, or rape, even. And then, over the years there’s also the lack of enforcement of those laws, even the ones that existed. The complete lack of enforcement of harassment, which is what we’re seeing now. And the covering up and this reemergence of the same mentality – which never went away. The so called locker room mentality never went away around. Male attitudes towards the female body or gender and power… So much of masculinity performs itself by putting down women; conquests of women are what make you a man in the eyes of other men. So yeah, I think the #MeToo movement has been so important to so many people – men and women – who have been experiencing violence and harassment and victimization in so many contexts. And I think that a lot of what you hear now is: “well, but it has gone too far.” And yes, in any moment there are going to be errors or mistakes that people make, or things that happen that we can’t control. But there’s so much truth that’s coming out, and to minimize that by saying “it has gone too far” when it’s been going on for five minutes… It’s really insulting. Patriarchy went too far. And if we can sit around and say: “well, it’s not all men are bad”, then we should certainly be able to hear women and men talking about their experiences of violence. You can’t condemn everybody who’s saying that because one or two people may have not told something accurately or remembered something accurately. But it’s so complicated and there’s so much trauma that is buried, experienced in families and workplaces… It just doesn’t come out, you know. And we talked about it. It was broached in the 70s and in the feminist literature: the big truth telling and consciousness raising, telling our stories… It didn’t stop.

(A.C & S.C) – Thank you that was so great.

U.V – Thank you very much